In 1936, Hewitt Taylor wrote a series of articles for The Louisville Herald about various communities around Louisville. He wrote the following article about Shepherdsville on September 23.

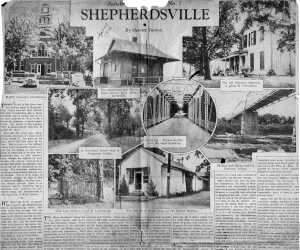

A facsimile of that newspaper article is pictured here. Besides the article itself, there are eight photos of scenes in and around Shepherdsville. To see a close-up of each image, select it from this list.

| courthouse | railroad depot | Coleman house |

| narrow bridge | main highway bridge |

| Salt River below bridge |

| lone grave | old stone bank |

There's no salt in Salt River—and you will find no sheep in Shepherdsville. These facts are fairly obvious. But there is something else in Shepherdsville and its vicinity that is not so easily disposed of. It is, to use a time—worn flippancy, a certain something. The answer to the question, Why is Shepherdsville, and why do people live there?

Don't get the wrong idea. Shepherdsville, you know, is a place you've always heard, of, It's quite on the map, and it has been there all the time. But it is not on the ordinary tourist route; automobile trippers, unless they are looking for old country hams or something of the kind, don't ordinarily head in that direction. And, though the highway is good enough, the narrow, cater—cornered bridge that pinch the approach from Louisville are no temptation to the tourist. The interurban, recently discontinued, stopped about half—way out, at Okolona. The L. & N. locals, in interurban fashion, do make a stop at Shepherdsville, but the Pan—American whizzes through. There is no business directly connecting Shepherdsville with Louisville—or elsewhere—except that Shepherdsville is the county seat of Bullitt County.

But there used to be. A century and a quarter ago, Shepherdsville was a manufacturing center. Salt licks which had brought first the game, then the Indian, then the white man, to its vicinity were but the outcroppings of deposits that produced deep salt wells, and the water from these wells, boiled in big kettles, precipitated salt. Salt from Shepherdsville or thereabout went down by boat to New Orleans and up by wagon train into Indiana, and even Michigan.

Then there was the iron works, right at, Shepherdsville, that worked into iron the ore from the Belmont mines, in the Bullitt County hills. The mines are abandoned now; richer ore and more profitable processes have been developed elsewhere. But Shepherdsville was making iron when the railroad first came through and claims credit for the first iron rails manufactured west of the Alleghenies. And Belmont is still a station on the L. & N., seven miles south of Shepherdsville.

There was a tannery, too, and other enterprises, Local, historians assert that along in the early eighteen hundreds, men with an eye to business moved out from Louisville, seeing in Shepherdville a coming "metropolis of the West."

In the history of nearly all the towns around Louisville, there is the repeated reminder that Louisville, in the very early days, was not a healthy place to live in. So the pioneers, and a good many of those that followed, got back into the hills. There are plenty of hills in Bullitt County, as everybody knows, or as anybody can see from the southern edge of Louisville. And Shepherdsville itself, though on a rise rather than a hill, is about as high as the highest hill in Jefferson County.

There is the usual Boone tradition in the neighborhood of Shepherdsville, only D. Boone is said to have carved his name on a rock at the fording of Salt River, instead of on a tree, and century and a half of seasonal high waters are blamed for washing the name, if not the rock away. But the record is still clear that in 1775 Thomas Hogan, Robert Croan, Isaac Skinner, John Dunn, Adam Cahill, one Moore, one Hoagland and several others, lured by the earlier pathfinder's reports of a most salubrious region, came from somewhere in the East and settled on Salt River. About this time, or a little later, Peter Shepherd came into the community.

In 1781 Peter Shepherd secured from the Commonwealth of Virginia a grant of 900 acres on the north side of Salt River, and therein laid out the town of Shepherdsville. Peter Shepherd had a son, Adam, to whom the town itself is credited by some historians, but there seems small question that the elder Shepherd in one way or another was responsible. In any case, Shepherdsville was well established before 1800; and the claim of this town, across the line in Bullitt, ranks easily with those of several towns in Jefferson County as being older, in fact, than Louisville.

Two others prominent among the very early settlers were Henry Crist and Nathaniel Cripps. These figured as leaders in the inevitable struggles with the Indians, and endured, harrowing experiences. Crist appears later in the record as General Crist, and still later as the representative to Congress from Bullitt County. In the local tradition, he was a very sturdy character, even for those days. In Cripps may be recognized another name that is not lost in history.

And when you say "settlers" in Shepherdsville, you mean just that. There are Hoaglands, Moores, Croans, Shepherds and others of the original families still in Shepherdsville or Bullitt County. And still others who came in later to stay, or still keep up their connections there.

In the fairly early history of Shepherdsville, old Paroquet Springs stands out in brilliant color. Here for about 50 years, beginning in the early Thirties, was a fashionable watering place, vieing with the spas of Europe and at least equaling in renown any in this country, then or now. In the days before the railroad, gay parties came by coach and carriage from the North and South, and the summer season was a round of romance and festivity, There was a hotel of 150 rooms, a casino for gentlemanly gambling, and acres of parked forest, threaded by winding walks and drives. And of course there was the water, a mineral well said to contain medicinal properties in remarkable degree.

The hotel burned down in 1879, and nothing remains but the clogged well, an old house at one time occupied by the owners of the property, an unkempt forest—and the Lone Grave.

The Lone grave marks the first and foremost romance of the Shepherdsville saga. In the heart of the once—parked forest. approached now by nearly obliterated trails, you need a guide to find it. But find it you must, and hear its story, or Shepherdsville will think you are just another city tripper, with a soul possessed of only restless curiosity, or a mind obsessed perhaps with thoughts of country ham.

It seems that in the 40s the Springs were visited by a belle from some far Southern state, a belle of furbelows and flounces, of dark but fragile beauty. At the same season came a young gentleman from Massachusetts. Romance moved apace. In the shade of two tall cedars, or under the spreading boughs of a beech nearby, they plighted their troth. Parting tenderly at the season's close, she sped south, he north, to prepare for the wedding in the following year. It was to be at the Springs where their two young souls had come together.

But there came war with Mexico, and hot—blooded youth, even in Massachusetts, answered the call. The young man was killed in action at Vera Cruz. Grieving for her lost love and shattered romance, the maiden sickened and died. She had exacted from her parents a solemn promise; that she be carried back to Paroquet Springs, in dear Kentucky, and buried at the site of her plighted troth— no stone to mark the spot, but an iron rail to keep all but the soul of her lover from hovering over her grave.

So stands the Lone Grave today, guarded by a small square of rusted iron fencing, but otherwise unmarked and uncared for. Still the romance lives in Shepherdsville, and still the story is fondly told there, with a tender if, sometimes, a whimsical smile. — Romance of an altogether different quality is that suggested by the lovely old Coleman home, "The Meadows," set about a half—mile back, along a straight, tree—bordered lane, from the highway approaching Shephersville.

Back in 1848, young T. C. Coleman II, captaining, for the experience of it, one of his father's line of river steamboats, saw tripping up the gangplank of his boat at Louisville Miss Dulcinea Payne Johnson, daughter of Capt. William Johnson, of Danville, setting forth on a trip down the river under the chaperonage of her parents. Said young Captain Coleman, on the instant, with all the gallantry of his Irish forbears, "I will marry that young lady!" And in the following year, he did.

The Colemans were well—established people; there was the iron business and there were other interests; steamboats were a sort of sideline. Soon T.C. Coleman II bought the old Fields place near Shepherdsville, and old—fashioned Southern mansion, with ample slave quarters and all comfortable appointments of the day, and thither he took his young bride. In time there were sons and daughters who went out into the world; all save Miss Alberta and Miss Ophelia, who happily remained, and still happily remain, to keep up the old house, in an atmosphere of lavender and old lace, of old silver and old mahogany—but in shy retirement from the world that speeds outside.

Meanwhile, T. C. Coleman II, come out from Louisville to take a big part in the affairs of Shepherdsville, has gone his way, leaving a substantial record of his own. And the Coleman name has been crossed with Dupont, with Marshall and with others who have not let it down—names that, for their large accomplishment, are known to anyone who read the public prints. So, dear ladies, the chronicler does not feel altogether guilty of unwarrantable intrusion into your proper privacy. But he'd like to write a book about you and your house.

An older house, the Old Stone Bank, and much the oldest building in Shepherdsville, stands on Shepherdsville's Main Street, freshly whitewashed and window—curtained by young Robert Hardy—in working hours of Louisville—and his wife. It makes a pretty cottage. Mrs. Pearl Lee, who owns the house now and who, through old—time associations, is one of Shepherdsville's historians, is commendably careful in her claims, but by popular repute the little stone building once housed the First Bank West of the Alleghenies. It looks substantial enough, at least, to bear this title.

Shepherdsville is not particularly distinguished by the structural remnants of another day. Perhaps its history goes too far back; anyway, it is more concerned with its aspect as a modern town. Nor are its modern residences overly pretentious. It is rather a town of comfortable homes. A modest place that yet attracts the eye is that of Cassius Marcellus Clay Porter, former county judge, who lives at a turn of the road just cross the main highway bridge near old Salt River Station. Another, on a shady street in Shepherdsville, is the home of "Tot" Carroll, lawyer, who with his wife are leaders in the town's affairs. Mr. Carroll is a nephew of Judge Tony Carroll of Louisville. Present County Judge C. P. Bradbury lives across the street from the Courthouse in another very comfortable place. Judge Bradbury, an ample man, is organized for comfort; and it certainly is not contempt of court to envy his philosophy.

The Merriman brothers—four of them—operate a general store business that includes about everything from the cradle to the grave, one of the four operating the farm from which is drawn much of the store's supplies. Other storekeepers in Shepherdsville, who specialize in this or that, will not begrudge this passing mention of one of the town's long—established institutions.

Shepherdsville has two banks, two barber shops, and two hotels. It used to have two newspapers, but Editor J. W. Barrall, of the Pioneer News, coming along some years ago with the opposition paper, bought the old—timer out. Associated with Editor Barrall at one time, but the way, was Attorney Wallace McKay, then and now of Louisville, but with his roots in Shepherdsville and Bullitt County. Mr. McKay's grandfather, Dr. Samuel Adams McKay, was for 50 years the principal physician of Shepherdsville and vicinity, for a long time including in his practice old Paroquet Springs.

Editor Barrall tells, with still painful reminiscence, the story of Shepherdsville's one outstanding tragedy, which he witnessed, December 20, 1917. Shoppers in Louisville were returning to Shepherdsville and other points along the line of the old Accommodation train. It was 30 minutes late. Missing the siding where it should have waited, it had just stopped at Shepherdsville. Suddenly No. 7, the L. & N.'s old Cannon Ball Express, now replaced by the Pan—American. came screeching into the peaceful Christmas scene. Ploughing through the Accommodation, it littered the snow—covered landscape with more than 60 broken bodies and all the pretty paraphernalia of their Christmas buying. Stores, churches, homes, of Shepherdsville were crowded with the dead and dying, laid in ghastly rows. Hardly a family in Bullitt County but was touched, in some way, by the tragedy. It was disaster more concentrated in effect than in the Great War, then accustoming many communities to widespread desolation.

But Shepherdsville likes to talk about today. It points with pride to the facts that its every house is occupied, and more are building here and there. It is getting used to its new municipal water works, for which its up—and—coming town board caught the the aid of the PWA. It takes for granted its electric street lighting, brought 20 miles from Louisville.

Now if something is done to route the new Southern Highway through Shepherdsville, the movement for which is already well under way. It is shorter, says Shepherdsville, than Dixie Highway—and anyhow, in old stage—coach days, it used to come through here.

Maybe this will fix the old, tricky, cantilever bridges coming out from Louisville; certainly this, or something else, should straighten out at once the incredible hazard of the high cater—cornered bridge at Gap-in-the-Knobs in the northern approach, and the deadly swing into the underpass on the south. For, if there is anything in present indications, more and more folks will want to come to Shepherdsville.

Perhaps the chronicler has not explained why people like to live in Shepherdsville; why certain Louisville people, finding something to their liking, have always established a comfortable basis there; why gradually increasing numbers make the 20—mile trip twice a day. And why, regardless of this, Shepherdsville keeps its own individuality and is essentially independent and self—contained. Perhaps the answer to the first "whys" is the last one. The chronicler, to whom the trip to Shepherdsville was something of an exploration, can think of no better reason.

This is a work in progress. The web page is copyright 2007 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved.

If you, the reader, have an interest in any particular part of our county history, and wish to contribute to this effort, use the form on our Contact Us page to send us your comments about this, or any Bullitt County History page. We welcome your comments and suggestions. If you feel that we have misspoken at any point, please feel free to point this out to us.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/bchistory/shep1936.html